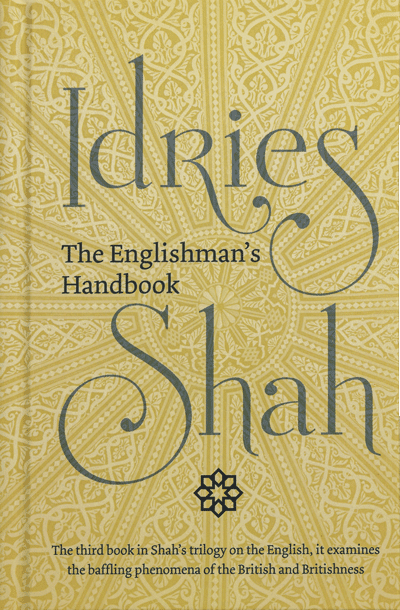

This is the third book in Idries Shah’s best-selling and humorous trilogy on why the English are as strange as they are.

The Englishman’s Handbook examines the ‘baffling phenomena of the British and Britishness’.

It presents a manual of handy tips on how to be like a local and ‘muddle through’ as a visitor to English shores, while also providing information to Brits on outsiders and ‘how to deal with them’.

Drawing on anecdotes, cultural observations, and examples from the press, the book contains extraordinary information on how to confuse visitors with the incomprehensible logic that is sheer Englishness.

An illuminating and often hilarious read, The Englishman’s Handbook is just as valuable to the British as it is to foreigners.

Foreword

1 The Questions They Ask

2 Aversion Therapy

3 The French

4 The Spanish

5 The Americans

6 The Lights – and the Dogs!

7 Masterly Inactivity

8 Teapoys and Boiled Potatoes

9 Say It Loud Enough and They Won’t Believe It...

10 Travelling, Visiting, Empiring

11 Not a Person, But...

12 Culture at a Distance

13 Dealing With Foreigners I: Disinformation

14 Dealing With Foreigners II: Scaring Them

15 Joining the Third World

16 Contrary to Expectation

17 Mr Thomas’s Fruit

18 Doublethink or Doublespeak?

19 The Foreignness of Foreigners

20 How Horrid IS Abroad?

21 Loathsome or Lovable?

22 Can Foreigners Deal With the British?

23 Life in Britain

24 Alarm and Despondency

25 Secret Meanings, Hidden Hands…

Notes

THE AMERICANS

The Brits call all Anglo-Saxon North Americans ‘Yanks’. This is a mistake – the Southerners hate the tag and snarl when they hear it. Canadians are North Americans, too, but they like it even less than the Southerners if you call them Americans.

You can tell the difference between Canadians and United States citizens, however, by a simple test. Get your candidate to say ‘How now, brown cow’. The Canadian is the one who says his or her ‘ow’ rather like the people of Oxfordshire or Bucks do in England.

In any case, I shall feel free to follow the august example of the OED and refer to United States citizens as ‘Americans’.

As the English have discovered, the best way to deal with the (United States) Americans is to confuse them with words. Since the UK and USA usages are often different, you can achieve a great deal at negligible cost.

Americans are generally credited with trying to impress you. If you suspect this, await your chance. For some reason, this next ploy works well with name-droppers.

When your American says, for instance, ‘I was invited to stay at the Kennedy home...’ interrupt at once. Your opportunity has arrived. As you know (and the American probably doesn’t), when an Englishman refers to a (something) ‘home’ he almost always means an institution, which is no such thing. Indeed, it’s likely to be something like a facility for the psychologically disadvantaged, as in ‘you’d be far better off in a home’.

All you need to say is, ‘What were you diagnosed as having, then?’ in a very sympathetic tone.

You can carry on with reminiscences about sad cases you have known, until he has roared out his disclaimer. Then all you need to say is: ‘Home? You mean... Oh, I see: I’m awfully sorry.’

By then, of course, it is too late for your name-dropper to retrieve the situation.

Mud sticks. However unjustly, there will be some people present at any social occasion where this gambit is played who will be vaguely sure forever after that at some time your unfortunate American was not exactly a hundred cents on the dollar.

The dollar. Americans concur with the English in accepting this unit of exchange as of paramount importance. English people will often refer to ‘64,000-dollar’ questions, just as if this old Teutonic unit were still their own... Dealing with Americans, especially on their home turf, requires a proper familiarity with it.

In the first place, it is pronounced daala. A daala is divided into 100 cents. These are often called pennies although, of course, they are not pennies at all.

One daala is also divided into 20 nikulz, which are equal to ten dymz – because a nikul is 5 pennies and a dym is ten pennies.

For some reason yet to be determined, the daala is derived from the German Thaler (as is the penny from the pfennig) but the cent is taken from the French: research into this anomaly continues.

Since you, the English, have got rid of the guinea, crown, half-crown, florin, groat, and so on, you can afford to be fairly complacent about money when dealing with Americans...

Now, of course I know that much British ‘small’ change is so heavy that mending trouser pockets has become a growth industry. And that other coins, such as the five-pence piece, are so small that the newspapers warn against letting small children choke on them. But you are in with a chance when scoring points about currency. If in doubt, as the English saying has it, bluff it out... Attack is the best form of defence.

From The Englishman’s Handbook by Idries Shah

Copyright © The Estate of Idries Shah

Idries Shah was born in India in 1924 into an aristocratic Afghan family. He was an author and teacher in the Sufi tradition and is considered one of the leading thinkers of the 20th century.

Shah devoted his life to collecting, translating and adapting key works of Sufi classical literature for the needs of the West. Called by some 'practical philosophy' - these works represent centuries of Sufi and Islamic thought aimed at developing human potential. His best-known works include the seminal book The Sufis, several collections of teaching stories featuring the ‘wise fool’ Nasrudin, Reflections and Knowing How to Know.

Shah's corpus - over three dozen books on topics ranging from psychology and spirituality to travelogues and cultural studies - have been translated into two dozen languages and have sold millions of copies around the world. They are regarded as an important bridge between the cultures of East and West.

UK Paperback

ISBN: 978-1-78479-198-8

Language: English

US Paperback

ISBN: 978-1-78479-201-5

Language: English

UK Hardcover

ISBN: 978-1-78479-864-2

Language: English

US Hardcover

ISBN: 978-1-78479-865-9

Language: English

UK eBook

ISBN: 978-1-78479-200-8

Language: English

US eBook

ISBN: 978-1-78479-203-9

Language: English

UK Kindle

ISBN: 978-1-78479-199-5

Language: English

US Kindle

ISBN: 978-1-78479-202-2

Language: English

UK Large Print

ISBN: 978-1-78479-862-8

Language: English

US Large Print

ISBN: 978-1-78479-863-5

Language: English