Sufism and Idries Shah

Sufism: The Classical Masters

The Classical Masters

Peter Brent

It is impossible to be clear about beginnings – a tradition

winds back through the centuries; one says, ‘Here it

commenced’ or ‘That was the man who spoke the first word’,

but however firm one’s tone of voice, however dogmatic

one’s assertion, one cannot lay bare the earliest, the primal

root. This is the more true the more imprecise the tradition;

it is absolutely true of a tradition in which from Master to

disciple there has been handed down through the generations

something as nebulous as an awareness, a manner of being,

a process of learning, an alteration of perception, the

development of an inner conviction, an imprecisely defined

method for achieving an incommunicable experience. Even

the word we have chosen to describe the tradition (not

one picked for that purpose by those whose tradition it

naturally was) is surrounded by a haze of discussion, even of

acrimonious argument.

What is the derivation of ‘Sufi’? It comes, say some,

from ashabi-sufa, ‘sitters in the shrine’, mendicants who

made their home in the porch of the temple and whom

the Prophet, Mohammed, used at times to feed. But even

those who accept this derivation dispute its meaning:

the ashabi-sufa, they say, were those who sat on benches

outside the mosques and debated matters theological with

the orthodox. Others choose a different root for the word,

settling on safa, ‘purity’ or ‘sincerity’, to mark the special

characteristic of those who set out upon the Sufi way. Some

believe that the Greek sophia, ‘wisdom’ or ‘knowledge’,

lies near the root of the matter. Many think suf, ‘wool’,

to be the relevant word for those who took to the selfdisciplined

life of the ascetic, wore long robes of wool,

cowled, distinctive and practical for a wanderer forced

often to sleep on the hard earth. But for others again, the

word needs no derivation, being simply itself: the sound

soof, they say, has its own power, a value based on the

universe’s hidden currents of meaning.

The debate over the name, however, is no more than a

surface indication of the more important dispute about the

origins of the Sufi teaching itself. This in turn concerns the

qualifications considered necessary in those wishing to learn

the Sufi way to self-development. Many commentators, indeed

most, insist that the tariqah, the Spiritual Path, is open only

to those who come to it by way of the shari’ah, the holy law

of Islam, based on the Koran and dependent upon theological

exegesis. Thus to be a Sufi you have first to be a Moslem.

The reason for this, they say, is that the origins of Sufism and

those of Islam are inextricably intertwined, and the Prophet

himself, as his profound mystic experiences prove, was not

merely a Sufi, but the first and greatest of Sufis.

If this were truly the case, then the ideas and practices

of Sufism would be, even in part, inaccessible to all those

who have not first adopted Islam. Yet writers and teachers

have for years busily spread the news of precisely these

ideas and practices throughout the West. Has their interest

been a purely scholarly one or, when it has not, have they

been either misguided or fraudulent in their endeavours?

J. Spencer Trimingham in his The Sufi Orders in Islam

writes that Sufis ‘differed considerably in their inner beliefs,

but their link with orthodoxy was guaranteed by their

acceptance of the law and ritual practices of Islam. All the

same they formed inner coteries in Islam and introduced

a hierarchal structure and modes of spiritual outlook and

worship foreign to its essential genius.’ It is a view that

suggests that an approach to the Sufi structure and modes of

action might not after all have to pass by way of orthodox

Islamic law. (One may not, on the other hand, have to go as

far as some and see the origins of Sufism, not in Islam at all,

but in such mystic traditions as those of the Zoroastrian

magi of Persia.)

What do the great names of Sufi tradition say? Jalaluddin

Rumi is still called, seven centuries after his death, Mowlana,

Our Master, by the Sufis, and not only the Sufis, of today.

He is, above all others perhaps, the essential voice of

Sufism, positive, unconventional, at times sardonic, at

times admonitory or anecdotal, his verse impregnated with

an awareness of profound love – but a love that makes it

sinewy, not sugary – and of the exaltation of transcendental

experience. He casts aside the trammels of theology when he

deals with the central, inescapable issue, the relation between

humanity and the divine:

I adore not the Cross nor the Crescent, I am not

Christian nor Jew...

Not from Eden and Paradise I fell, not from Adam

my lineage I drew.

In a place beyond uttermost place, in a tract without

shadow or trace,

Soul and body transcending I live in the soul of my

loved one anew.

The loved one here is both the Sufi guide and the divine

itself. And a contemporary of his, the Sufi Master Nafasi,

wrote of God’s proximity to mankind, ‘The beautiful truth

is that He is ever near to those who seek Him, regardless of

their creed or belief.’

Scholars argue that Rumi, and the other great thinkers

and teachers through whom Sufism developed, can only be

considered in the Islamic context within which they grew and

worked. It was that religion which they practised, its tenets

and rituals that they drew from and illuminated. And in a

broad sense this must be true, since we are all the products

of the cultures from which we spring. But to say that Sufism,

an approach to the Absolute by way of self-discipline,

heightened perception, retrained intelligence and profound

emotion, must be restricted to those who come to it through

the gateway of Islam’s shari’ah seems on the face of it almost

perversely narrow. When, in the mid-14th century, the ruler

of Fars decreed in an excess of puritan zeal that all the inns of

the town must close, Hafiz, among the greatest of Sufi poets,

and one who understood better than most the metaphor

‘God-intoxicated’, wrote:

They have closed the doors of the wine taverns;

O God suffer not

That they should open the doors of the house of

deceit and hypocrisy.

If they have closed them for the sake of the selfish

zealot

Be of good cheer, for they will reopen them for God’s

sake.

And what is one to make of this short tale from Rumi’s

Discourses? ‘I spoke one day to a group of people, among

whom were some non-Moslems. In the midst of my speech

they wept and experienced ecstasy. Only one out of a

thousand Moslems understood why they wept. The master

then declared: “Although they do not understand the inner

spirit of these words they comprehend the underlying feeling,

the real root of the matter.”’ If we who are not Moslems

listen carefully, may we too not comprehend ‘the root of the

matter’?

It seems likely that certain elements in the Sufi tradition are

indeed older than Islam itself. It is hard to believe that a mystic

tradition should have had a sudden untrammelled beginning

in the 7th century, without being heavily influenced by existing

ideas, especially when one remembers that Islam itself is a selfaware

continuation of the monotheism already long developed

in Judaism and Christianity. There is also the discomfort with

which, as Trimingham and others have suggested, Sufism

seems at times to sit within Islam, a consequence perhaps

of the incompatibility between the religion of revelation and

the religion of continuing mystical experience. A once-for-all

appearance on the human plane of the divine, as postulated

by Christians, for example, tends to be codified in precepts,

transfixed by tradition and animated only by ritual; on the

whole, later generations are not permitted to obscure it by

their own directly personal experience of the Absolute. Yet

in Islam, both traditions co-exist, suggesting that some part

of the mystical convention may have its beginnings not in

the primary prophetic Message, but elsewhere. For that

convention supplies legitimacy to its adherents, equivalent

to that supplied by revelation to the theologians, through

a continuing chain of inductor and inducted, linked always

by the relation between an unforced authority and a willing

submission, and stretching back across the centuries. It is

this chain of Master and disciple, known in Sufism as the

silsilah, that itself provides the necessary authority for the

latest neophyte desiring to add his link to it.

The Master personifies that authority, as he does the inner

experience which is both the basis and the purpose for that

authority’s existence. Again, such systems of tuition, where

they exist elsewhere in the world, in Hinduism’s Guru-shishya

parampara, for instance, have their roots in a pre-literate

world where all instruction had to be oral, and those who

taught were therefore the living embodiment of the culture

they transmitted. There are many other reasons, of course,

why tuition in mysticism should be by means of a similar

direct transmission, and yet one wonders whether its very

structures do not reveal how very deep and ancient the roots

of Sufism are.

The argument, however, has centred on what the exclusive

origins of Sufism might be. One profound lesson that the

philosophies of Asia can teach is that many desperate

disagreements based on the disruptive ‘either–or’ of which

scholastic thinkers are so fond can be resolved by a reconciling

‘both’. This is probably such a case. If historical Islam itself

has its roots in monotheism already well known in Arabia, so

may Sufism have arisen out of already established mystical

schools. Yet the story of Mohammed and his mission, of his

relation with the divine and the transmission of the Koran,

is, of course, one in which profound mystical certainties

are both implicit and explicitly described. Nor is there any

question that the images and metaphors, the philosophical

concepts and cultural counters of the Sufi sages have always

been those of Islam. It seems probable that, like so much

else, the beginnings of Sufism are multiple, complex: as Idries

Shah writes in his The Sufis, ‘That is why, in Sufi tradition,

the “Chain of Transmission” of Sufi schools may reach back

to the Prophet by one line, and to Elias by another.’ Nor need

there be any conflict between the mystics and the orthodox:

‘Because the Sufis recognised Islam as a manifestation of the

essential upsurge of transcendental teaching, there could be

no interior conflict between Islam and Sufism. Sufism was

taken to correspond to the inner reality of Islam, as with

the equivalent aspect of every other religion and genuine

tradition.’

Like all mystical doctrines, Sufism (a term, incidentally,

unknown until recent decades – it was coined by a German in

the 1820s – and thus never used by the famous Sufi poets and

philosophers of the past) postulates an Absolute and goes on

to assert that we can attain an awareness of it. This Absolute

has been defined in terms both secular and religious. It has

been called the Reality of Existence, the Reality of Being.

Being is of its nature singular, since nothing that exists does

so to a greater degree than anything else: it either is or it is

not. This singularity is the Divine. Set within the ideologies of

Islam, it becomes specific. Personified, it becomes the object

of a transcendent love. Yet one may ask, how can there be an

object when the devotee, too, is necessarily part of and one

with the cosmic unity?

It seems, therefore, that we face a paradox: God is separate

from the worshipper, and at the same time is the worshipper

himself; the passionate element in Sufism (like that of the

Hindu bakhtis) can only come from a perceived duality

that acts as a barrier between God and the worshipper. It

is the barrier itself, however, that resolves this paradox: its

resistance sets up precisely the intense devotional energy

which the worshipper must develop in order to burst through

it. Beyond lies that in which no paradox survives: the intense

awareness of oneness, of the magnificent unity of the cosmos,

absolute and indivisible. This perceived singularity, in which

at one level one remains oneself, at another one totally loses

oneself, is the Real, and it is with this Reality that Sufism is

concerned. To reach it, to understand it, to see it clearly – in

different words, to reach and understand God – is the object

of its disciplines.

At the end of the Sufi path, therefore, as at the far limit of

other spiritual or mystical processes, there seems to lie an alldevouring

blaze in which duality and self both vanish. And

the pathway is marked, both in general terms and with the

special signposts of Sufism. Professor A. M. A. Shushtery in

his Outlines of Islamic Culture tells us, ‘A Sufi believes that it

is by purifying his heart and not by observances of religious

rituals, or prayer or fast, one can realise the truth... It is through

self-discipline, devotion, virtue and intention that one can

know his God. This stage is called fana-fil-lah or annihilation

in God...’ The route is by way of maqam, translated as

‘stations’, each of which corresponds to a particular spiritual

attainment. Also on the way are experiences of ecstasy – hal

or ahwal, meaning ‘state’ or ‘states’ – which, like the stations,

have finally to be transcended. The stations are reached by

a series of exercises prescribed by one’s Teacher, but for the

experience of hal there is no prescription. ‘Hal,’ wrote Ali

al-Hujwiri in the 11th century, ‘is something that descends

into a man, without his being able to repel it when it comes,

or to attract it when it goes...’

Yet in Sufism one often comes across mistrust not only of

the stations as ends in themselves, but also of the ecstatic

states. It is not that they are considered spurious; on the

contrary, it is precisely the genuineness of the divine energy

that makes Sufi writers doubt the fitness of those minds that so

abruptly and sometimes so catastrophically receive it. It is as

though the Sufi path had on either side of it pleasant bowers,

shady places, welcoming groves, and in each of these there

was a group of people murmuring to each other, ‘See? We

have arrived.’ Some repeat certain exercises, convinced that

to continue in this way is the object of their journey. Others

again stand with eyes rolled up, or whirl with widespread

arms, or roll on the ground, a light froth upon their lips; they

cry out the names of God and feel themselves filled with a

divine response. Yet, faintly, perhaps through difficult country,

perhaps up an ever-increasing slope, the path winds on and

the traveller truly concerned to reach its end must leave these

others behind, each of them comforted by apparent certainty,

each of them deceived. It is he, stubborn in his quest and

not disturbed by the passage of the years or the hardships

of the journey, who has the only chance of reaching the true

goal. Writing in his Revelation of the Veiled, Ali al-Hujwiri

tells us, ‘All the Sheikhs of the Path are agreed that when a

man has escaped from the captivity of the “stations” and gets

rid of the impurity of the “states” and is liberated from the

abode of change and decay and becomes endowed with all

praiseworthy qualities, he is disjoined from all qualities.’ In

other words, beyond maqam, beyond hal, there is another

state, the condition of peace, of self-realisation, partaking

of the cosmic unity; that final state he calls tamkin. Seen by

one in that stable condition, doubtless the followers of the

exercises seem little better than apprentices, while those in

the grip of ecstasy must appear simply unprepared, unready

for the force that has entered them. Thus what in many other

traditions would be taken as proof of a spiritual journey

properly undertaken and joyfully completed, indicates to

Sufis little more than that the journey is under way.

A bewildering array of sages, saints and self-styled masters

moves towards us from the recesses of Asia, and we may be

forgiven when in our minds their several doctrines begin to

merge into one ill-defined, if attractive, mish-mash of reachme-

down exoticism. Yet we should be careful: each tradition

has been moulded by its own centuries, and by the society

from which it has sprung. If we are to deal with the Hindu

guru, for example, we must remember that reincarnation

and the concept of karma are of the essence of his teaching.

With the Sufis, as we have seen, it is Islam that provides

the terminology and much of the ritual. The Buddhists of

Tibet and those of the discipline we know as Zen wrap their

teachings in the preconceptions and vocabulary of the lands

where those teachings developed. Each tradition appeals in a

different way, demands a different kind of discipline, suggests

its goals in different terms. There is in the end, it seems, no

‘Eastern philosophy’, no ‘Asiatic religion’.

The difference between one and another discipline may

be crucial, either for an individual’s own development or,

possibly, for the development of the West as a whole. If it

is true that the people of Europe, and those whose cultures

stem from that of Europe, are now in a new condition of

bewilderment and doubt; if it is true that Christianity, a

religion of ethics and of revelation, cannot become again

what it was before scientific materialism routed it; if it is

true that more and more Westerners are embarked upon the

search for an individual experience of the transcendent, and

upon the self-discovery that must both precede and follow

that experience; if all this is true, then the attitude that we

take up now to this or that particular teaching may well

have repercussions over many years. Our Western culture

is changing and, threatened or excited by that possibility,

we have begun to look beyond the borders of the West for

guidance. It is necessary that we look clearly and learn to

distinguish between the various solutions suggested by the

cultures and traditions which we may examine.

Mircea Eliade in his essay Experiences of the Mystic

Light* writes, ‘In the course of human history there have

been a thousand different ways of conceiving and evaluating

the Spirit... For all conceptualisation is irremediably linked

with language, and consequently with culture and history.

One can say that the meaning of the supernatural light is

directly conveyed to the soul of the man who experiences it –

and yet its meaning can only come fully to his consciousness

clothed in a pre-existent ideology.’ It is the present dilemma

of the West that it has no such pre-existent ideology; the

politics of ecclesiastical domination and the essential dualism

of Christianity have reduced the cultural impact of the

monistic experience of the mystics to relative insignificance.

The separation made by religion between Mankind and God,

and by science between Mankind and Nature, has denied us

a framework for any notion of cosmic unity, even for any real

conception of an inner self not couched in the arid terms of

psycho-analytical theory. If we are to pursue such a notion,

such a conception, it seems to me we had better try to do so

through disciplines that fit in as nearly as possible with those

ideas, about society, about culture, about the spirit and about

the cosmos, that we have developed.

It may be that an implication of the greatest significance

to the West is contained in one of the names by which Sufis

are known: Ahl al ishara, ‘Those who learn by allusion’. For

Sufi preceptors it is the effect of their teaching, and not the

teaching itself, which is of the first importance. Not what

is said or done, but what happens to the listener as a result

of what is said or done, is the Teacher’s primary concern.

* Published in The Two and the One, London 1965.

What a Sufi says or writes need not be factually true; it is an

instrument intended to work upon the minds of those who

come across it. Metaphor, hyperbole, joke or boredom, all

these are tools that the Sufi Master may use to harmonise

with his disciples. For this reason, quite apart from the

prevailing priorities of Islamic and especially Persian culture,

many of the great Sufi luminaries of the past have been poets.

So often active at levels more numerous and deeper than we

are conscious of, able at times to yield layer after layer of

meaning to our fascinated scrutiny, lingering in the mind

with an echoing after-impact that sometimes lasts as long as

memory itself, poetry is the ideal medium for those who want

to move us as it were obliquely, through allusion.

As a result, those who follow the Sufi path soon begin to

learn in a manner new to them. The process of learning itself,

rather than anything factually learned, begins to alter them,

to alter the way they think and the way they perceive the

world. Long before the Sufi way turns into a purely mystical

discipline therefore, it works at the level of the intellect and

the imagination. Its first stages are intended to prepare one

for the later experiences, in order that one should not mistake

their nature. Properly directed by a teacher who understands

his individual needs, the disciple will achieve the sought-after

ecstasy central to mysticism only when completely ready for

it. Then, far from overwhelming him, it will complete him.

It is not for nothing that Sufis, therefore, equate the

Absolute with Reality. The process of learning is the process

of discovering what really exists. In order to do this, the

neophyte upon the path must be persuaded to use his senses,

his intelligence and his imagination in a new fashion. He

must be helped towards a new kind, as well as a new level,

of consciousness. Here Sufism, like certain other similar

disciplines, begins to link with present developments in

psychology. As Professor Robert Ornstein has written in

his The Psychology of Consciousness, ‘We know... that our

“normal” consciousness is not complete, but is an exquisitely

evolved, selective personal construction whose primary

purpose is to ensure biological survival. But this mode,

although necessary for survival, is not necessarily the only

one in which consciousness can operate... The automatisation

of ordinary consciousness is a trade-off: for the sake of

survival, we lose much of the richness of experience... The

deautomatisation of consciousness is the key. It enables us

personally to note factors which had previously escaped

attention. It is here that the work of the esoteric traditions is

most fruitfully incorporated into Western science.’ The many

automatic responses we make to our environment, although

necessary for sanity and efficiency, stand between us and the

world’s reality. To reach the real, we have to learn to respond

to it; we have, in other words, to become real ourselves.

A way in which one may differentiate between various

mystical traditions is to see what attitude they take to reality –

the hard, intractable reality of the physical and social world

we all inhabit. One view is that of Hinduism, which conceives

of the undifferentiated unity glimpsed during the ecstatic

experience as the only true reality; it therefore insists upon

the illusory nature of the differentiated world available to

ordinary sense-experience. The disciples of the spiritual guru

are enjoined, as are in the course of time all orthodox Hindus,

to withdraw from that illusory world and to base themselves

upon the cosmic unity that is Brahman. If everything is finally

one, then family attachments, relationships, activity in the

world, all of which reflect subject–object dependencies, must

be fundamentally misguided. The disciple therefore casts them

off, removes himself to an ashram, and there attempts to match

the singularity of the cosmos with his own. Withdrawal of a

similar nature, to hermitage and cloister, marks the history

of Christian mysticism; for reasons practical and political,

as well as philosophical, it has largely been the preserve of

the enclosed orders – or else, by definition of the Church, of

heretics.

The whole burden of what such disciplines teach is that the

serious person, the person dedicated to the search for ultimate

reality, must turn away from the illusion of differentiated

‘normality’, as a Hindu might say, or from the temptations of

the world, as a Christian might put it. Yet such withdrawal

is not necessary in other traditions. Zen Buddhists, for

example, while seeking samadhi, or the ecstatic annihilation

of self, do not make this the end of their endeavours. On

the contrary, writes Katsuki Sekida in Zen Training, ‘if you

want to attain genuine enlightenment and emancipation, you

must go completely through this condition...’ In his maturity

the student of Zen ‘goes out into the actual world of routine

and lets his mind work with no hindrance... If we accept that

there is an object in Zen practice, then it is this freedom of the

mind in actual living.’ This is the fourth category of samadhi,

the one that lies beyond mere ecstasy and, as we have seen,

Sufi beliefs too accommodate such a condition in that level of

consciousness called by Hujwiri tamkin, and elsewhere baga.

Although both Zen and Sufi teachings have led to the

formation of monastic orders, within which those devoted

to the ascetic life tend to their own spiritual development

and, perhaps, learn in time to help others through the same

process, many of the followers have always been laymen. The

Sufi orders have through the centuries of their existence been

surrounded by the non-monastics who were tied to them by

vows and ceremonies of initiation. In Islam above all there

can surely be no incompatibility between the secular and

the mystical life, when the Prophet upon whose Message it

stands was himself a merchant, a politician and a military

leader as well as a religious philosopher and a mystic. Indeed

the impact of Mohammed’s life depends upon the contrast

between his outer ordinariness and the blazing light of divinity

with which he was filled. Thus it comes as no surprise to find

a Sufi thinker, Abu Nasr Sarraj, pointing out as early as the

10th century that extreme asceticism could be as debilitating

to the spirit as luxury, and doubting the value of the hermit’s

seclusion for the good reason that the sources of evil lie within

the self. Human beings, whatever their spiritual condition,

ought, he considered, to fulfil their obligations in the world;

self-illumination would make them even better able to do so.

From the beginning, therefore, a large proportion of Sufis

have maintained their connection with the ‘ordinary’ world,

and in the list of Sufism’s great men there stand many who by

no stretch of the imagination could be considered ascetic or

monastic. For them, the effects of what they knew, had seen

and understood were brought into play in their dealings with

the world about them. What they believed shone through

what they wrote and did. They had prepared their minds for

the mystical experience, and when it came, when it had filled

them, they became, not frenzied, but infinitely richer. That

wealth they then brought to bear on those around them, those

who came to them, those who heard and read their treatises.

It was yet another 10th century Sufi sage, Abu Bakr

al-Kalabadhi, who wrote, ‘If a man’s ecstasy is weak, he

exhibits ecstasy... If, however, his ecstasy is strong, he controls

himself and is passive.’ In that state of controlled ecstasy,

calmed inwardly by the certainty that only enlightenment can

bring, the Sufi is free to move about the world, to act in it, to

take his place in it, and often to excel in it. He has achieved a

new level of perception, a new kind of understanding, a new

breadth of consciousness, he has experienced the cosmos as

unity and so has understood his own significance: he is the

enlightened man.

It is no wonder that the great luminaries of Islam, whose

works no passing of the generations seems able to diminish,

have in so many cases been Sufis. As we have seen, it is claimed

even by the most orthodox doctors of religious law that the

first Sufi was the Prophet himself. But the long line of the

distinguished winds down the centuries of Islam as though

by their brightness to mark out the path of their tradition.

That is not to say that with each of them the tradition made

a greater or lesser degree of ‘progress’, but rather that each

lights that segment of the path where his illumination will be

of the greatest use.

Nevertheless, Abu Hamid Mohammed el-Ghazali

must stand as the figure, reconciliatory, scholarly, deeply

philosophical and profoundly religious, with whom Sufism

made a new beginning. It was he who gathered together

the doctrines and ideas of his Sufi predecessors, selected,

synthesised, and finally reconciled his conclusions with the

orthodoxies of Islam. But underlying his patient and creative

scholasticism there burned a constant, mystic fire, and the life

that he breathed into the academic clay, once he had gathered

it and kneaded it into shape, was that of the Sufi certainties.

Born in north-eastern Persia in 1058, he was brought up

and educated by a Sufi master. Before he was thirty-five he

had been appointed to the Chair of Philosophy and Theology

at Nizamiyya University, one of the great establishments

that made Baghdad the centre of Islamic culture. Although

el-Ghazali, the youngest of the university’s professors, was

instantly acclaimed, he turned his back on fame and success

after only five years. It was not that he disliked praise, indeed,

he confessed that he liked it too well, but rather that he had

come to the end of what he might usefully arrive at through

the techniques of scholasticism, had reached the limits, both

as student and as teacher, of what in the academic world had

value for him.

As he wrote later, ‘I next turned with set purpose to the

method of Sufism. I knew that the Sufi way includes both

intellectual belief and practical activity... The intellectual

belief was easier. But it became clear to me, however, that

what is most distinctive of mysticism is something which

cannot be apprehended by study, but only by immediate

experience, by ecstasy and by moral change. I apprehended

clearly that the mystics were men who had real experience,

not men of words, and that I had already progressed as far as

was possible by way of intellectual apprehension...’

In the work he was yet to do there would be, within the

academic integument that gave it both form and legitimacy,

an elusive other certainty baffling to scholars, a hint of secrets

which, although by their nature no words can communicate

them, he was taken wilfully to have left unrevealed.

Nevertheless he was to write and speak a great deal, his works

finally becoming among the most influential ever published.

After wandering for twelve years (the classical period of

dervish training), during which he ‘had no other objective

than that of seeking solitariness, overcoming selfishness,

fighting passions, trying to make clear my soul, to complete my

character’, he returned, changed but active, to the world. The

work he did during his lifetime earned him the amazing title

of The Authority of Islam; but after his death his work spread

even wider than the religion’s boundaries. He had woven

into his philosophy the ideas of both Jewish and Christian

mysticism, had adapted the transcendental world-scheme

of Plotinus and the neo-Platonists; now his new synthesis,

fruitfully translated, returned these theories and certainties,

embellished and increased, to the cultures from which he had

drawn them. In Hebrew and Latin his books spread through

the academies and among the churchmen of Europe. That

13th century imperial genius, the Hohenstaufen Frederick

II, as Holy Roman Emperor the ruler of Sicily (and happily

engaged there in creating his own synthesis between Europe

and the Middle East), had el-Ghazali’s books translated into

Latin. St Thomas Aquinas, another great synthesiser, drew

on his theories, as he did on those of the pagan Plotinus.

El-Ghazali, known to the Schoolmen of the West as Algazel,

became a figure central to the work of the universities of

Padua and Bologna, and later of other Italian centres of

learning. A few years on, Occam, whose ‘razor’ logicians

still like to flourish, was basing much of his anti-scholastic

views on el-Ghazali’s treatises. The ascetic struggling in the

arid depths of Syria with the problems of self-development

had become, posthumously and perhaps despite his wishes,

a world figure, and paradoxically one often beloved of the

very academics who by their training were perhaps among

the least able to understand him.

El-Ghazali’s was a liberating effect upon Islamic thought.

The increasingly narrow orthodoxies of the doctors of law

were challenged and, indeed, superseded by the refreshing

speculation he pioneered and endorsed. His attitude to

philosophy opened new approaches to religion, as well as to

other facets of human spiritual and psychological existence.

His belief that thought was natural and right was reinforced

by his conviction that human will was free and that human

beings had the God-given ability to choose between

alternatives. However, he went beyond both philosophy and

active choice in his certainty that the ultimate perceptions

take place in the condition of ecstasy, and that the reality then

perceived takes precedence over anything else mankind may

know. For this reason, both theology and philosophy had

to be finally subordinated to personal experience, through

which a person may achieve revelations more piercing and

direct than any truth arrived at by mere ratiocination. But

in the end, like all great spiritual teachers, he was not his

doctrines, but was in himself the truth he taught. What he

knew with the very centre of himself no words could describe

or pass to anyone else. In his Revival of Religious Sciences he

wrote, ‘The question of divine knowledge is so deep that it is

really known only to those who have it. A child has no real

knowledge of the attainments of an adult. An ordinary adult

cannot understand the attainments of a learned man. In the

same way, a learned man cannot understand the experiences

of enlightened saints or Sufis.’ One can only write what can

be written; for the rest, one either is it – or one is not.

Jalaluddin Rumi, whom Sufis call ‘The Master’ and

Professor Fatemi entitles ‘The Light of Sufism’, was born in

Balkh, now in Afghanistan, in 1207. His father was a famous

scholar and theologian, so that Rumi’s early training was

in the rigorously classical and logical modes. When he was

twelve his family left Balkh and, after some time spent in

travelling about the Middle East, finally settled in Konia,

anciently Iconium, in what is now Turkey. Rumi married, was

left a widower, married again; from both marriages he had

children. He early became a teacher, but soon he was himself

wandering through western Asia in the company of a Sufi

master named Burhan al-Din, his task now self-development.

When after some years he returned to Konia, he resumed

the teaching of theology, but added to it a new spiritual

resonance through the guidance he was able to give. As a

result, he quickly achieved a position of great religious – and

thus, in Islam, social and even secular – importance. When he

was at the height of this relatively conventional fame, he met

the Sufi teacher, Shamsuddin of Tabriz.

This strange and powerful man, who seemed to some no

more than a noisy, arrogant blusterer, at once dislocated

Rumi’s life. In the esoteric traditions of Asia, relying as they

do on the transmission of a mystic essence from a teacher to a

disciple, there occurs again and again that moment of recognition

in which Master and student understand – wordlessly,

at once – that they are destined to work together. Such a

moment evidently occurred between Rumi and Shamsuddin;

the revered theologian, seized with an intoxication that

expressed itself at times in solitary dance, placed himself

without reservation among the wandering Sufi’s pupils. As

his son wrote, ‘The great professor became a beginner in selfperfection.’

The orthodox criticised, bewailed the loss of their

teacher or decided simply that Rumi was mad. Shamsuddin

after fifteen months left Konia, but Rumi continued his

inward, intensely devoted progress. Perhaps then, perhaps a

little later, in 1248, Shamsuddin died, apparently in violence

caused by the jealousies and antagonisms Rumi’s ‘strange’

behaviour had provoked. Eventually, however, Rumi, who

was no longer to be deflected, reconciled the increasing pressures

of his inward search with the social demands of the

people of Konia, or, more accurately, reconciled the people of

Konia to the demands of his inward search, in part by guiding

them in their own.

To understand the role that Shamsuddin – internalised

by his pupil, his religious essence transferred – played

thenceforth in the life of Rumi, one must understand the

nature of the feeling that exists, in living mystical traditions,

between murshid and murid, guru and shishya, between

teacher and taught. The Master becomes a living metaphor

for the perfection of the Absolute. He seems for the disciple

at once the stepping-stone to divinity and, as a self-realised

man, divinity made flesh. At the same time there exists in

both the conviction that between them the transmission of a

quality, indefinable yet unmistakable, can take place, through

which the disciple will be permanently altered. When this

transmission has occurred, the disciple is in no doubt about

what he has gained, nor will the departure or death of the

Master diminish one iota of it: he has been flooded by a

perception of the Absolute so clear that almost nothing he

can do will make him lose it, especially since all he does is

done only in its light. In him, therefore, the fact of the teacher

and the fact of the divine merge into an inextricable whole,

fusing with his own essence to produce a new level of being.

Thus Rumi could write:

When I go into the mine he is the carnelian and

ruby;

When I go into the sea he is the pearl.

When I am on the plains he is the garden rose; when

I come to the heavens he is the star...

My master and my sheikh, my pain and my remedy;

I declare these words openly, my Shams and my God.

I have reached truth because of you, O my soul of

truth.

These lines come from his Divani Shamsi Tabriz; he was

now in the condition that Professor Arasteh has described in

his Rumi the Persian. ‘He was all love, all joy, all happiness.

He had no grief, no anxiety. He was totally born, totally

spontaneous...’

Rumi now felt able to set up a school of devotees of his

own, and in it to guide others towards that state to which

the fact of Shams had guided him. It was now, too, that he

probably began to work on that six-volume compilation

of fables, poems, tales, examples and speculations, the

Mathnavi, through which, perhaps more than anywhere else

in his work, he attempted to induce in the reader something

of his own state of mind; as Idries Shah puts it, ‘a picture is

built up by multiple impact to infuse into the mind the Sufi

message’. In the ‘Mevlevi Order’ was later codified what had

at times been his own practice of dancing, developing the

steady whirling which is at one level a mechanical aid to the

induction of trance, but is at another (I quote Shah again)

‘designed to bring the Seeker into affinity with the mystical

current, in order to be transformed by it’.

But for Rumi trance was, as it must be for a Sufi, no more

than a stage in the process of self-development. Again and

again, in the Mathnavi, in his Fihi ma Fihi and elsewhere, he

refers to the condition beyond trance, beyond belief, beyond

mere creed or doctrine.

Cross and the churches, from end to end

I surveyed; He was not on the cross.

I went to the idol temple, to the ancient pagoda,

No trace was visible there.

I bent the reins of search to the Ka’ba,

He was not in the resort of old and young.

I gazed into my own heart;

There I saw Him, He was nowhere else.

And, as he stated explicitly in the Divani Shamsi Tabriz, ‘I

have put duality away... One I seek, One I know, One I see,

One I call.’ This monism Rumi experienced directly, and he

interpreted the experience as love. He is above all the poet

of transcendent love; he saw it clearly and never made it an

excuse for rhetoric, imprecise although exciting. He had very

definite ideas about the nature of the human being, and the

struggle needed to transcend the polarity between reason and

instinct in order to reach, once again, the state of peaceful

certainty beyond. In that final condition, an individual was

able to integrate instinct and reason with intuitive perception

and the love that would both keep him whole and permit him

direct involvement with every aspect of the cosmos. Love, in

other words, became at this level a medium for perceptions

otherwise impossible to human beings. It is this vision of

the person evolved that remains immediate and full of

meaning. As we struggle earnestly to understand ourselves in

a world where we seem, at precisely the same time and with

precisely the same dedication, to be building endless barriers

and creating endless pressures, Rumi’s insights and oblique

admonitions are more relevant than they have ever been.

Born into a Sufi family almost exactly a hundred years

after El-Ghazali, almost exactly forty years before Rumi, Ibn

el-Arabi, like them, displayed great gifts even in childhood.

Brought up in the heyday of Arabic Spain (paradoxically, one

of the most civilised societies in European history) he studied

in Lisbon, Seville and Cordoba. All his life he wrote poetry;

in it, he often returned to the theme of human love – deeply

felt and magnificently described – used as a metaphor for the

transcendent emotion that lies glittering at the core of all his

work. Yet ‘metaphor’ does inadequate justice to the reality

he evidently experienced at both levels; either reading, the

sensual and the mystical, is a true reading. He was, indeed,

frequently attacked for being no more than a writer of erotic

poetry who sought to cover his indulgence by claiming a

spiritual meaning for it. The fact is that among the various

levels of perception and feeling experienced by the developed

person some are not less real than others, nor does the last

stage cancel all those that have gone before. Each is true in its

own way. The error is to imagine any one of them the total

reality. The divine is the only total reality, and that includes

all aspects, all levels.

Thus for Ibn el-Arabi his sensual response to feminine

beauty was real, not imagined; yet, precisely because of its

reality, he saw that beauty as a metaphor for the world’s

beauty, the beauty of nature, just as he saw in the relation

between men and women a metaphor for that between

humanity and God. For if Genesis is true, then woman is

made in man’s image as man is in God’s; thus, as God stands,

in love and concern, to his creation, Nature, so man stands

to woman. The feeling is real in its own terms, yet only

becomes complete in the metaphysical dimension. Today we

may reject Genesis and thus the metaphor may lose some of

its particular force, but it is at our peril that we reject this

awareness of the multiplicity of the real.

Ibn el-Arabi made such ideas explicit in his prose treatises,

for he was a scholar more complete even than his doctorial

critics. His explanatory notes to his love poetry seem to

have satisfied the most puritanical and rigorously orthodox

theologians that he had nowhere deviated from the approved

path of righteousness. Thus his encyclopaedic survey of Sufi

ideas, Futuhat-al-Makkiyya and his dissertation on various

aspects of Sufism, Fusus-al-hikam, like his other books of

theory and speculation, passed to succeeding generations not

as the outpourings of a heedless poet, but as the considered

works of a scholar acknowledged to be among the greatest

of his time.

As Rumi and other Sufis have, Ibn el-Arabi emphasised

(for example in Chapter XXII of Fusus-al-hikam) that

beyond fana, the mystical annihilation of self, there exists

another state in which that experience is, as it were, stabilised,

made permanent. It was because of his awareness of this

ultimate condition that he was able to accept the structures

of orthodoxy. He realised that within every such structure,

perhaps almost snuffed out by its weight but certainly once

ablaze, there could be found the flame of mysticism. All

great teachers – Moses, Jesus, Mohammed and others – had

embodied that flame, and though human perversity might

distort faith in the divine, as in the case of self-punishing

ascetics, yet any true religion might be the mystic’s startingpoint.

It is no wonder that throughout his life doctrinaire

scholars and theologians, like men in narrow valleys which

they believe to be the world, condemned his breadth of

understanding as the dangerous deviations of a heretic.

A near contemporary of Rumi, and as widely known

wherever Persian poetry is remembered and recited, is Saadi

of Shiraz. Born in 1184, he like el-Ghazali was educated at the

Nizamiyya University in Baghdad, studying there under the

Sufi sage, Jilani. Thereafter he spent many years wandering,

in the prescribed poverty of the dervish, through the Middle

East, North Africa, Ethiopia and Asia Minor. It was typical

of his troubled period that at one point he was captured

by Crusaders, and had to be ransomed. The price paid for

this incomparable poet, employed while captive as a trenchdigger,

was ten dinars.

Saadi’s most famous works, his Gulistan and Bustan,

‘Rose Garden’ and ‘Orchard’, are rich mixtures of aphorisms,

proverbs, love lyrics, erotic stories, descriptions of great

rulers and, above all, pronouncements in prose and verse on

morality and ethics, on the right role of rulers and the proper

attitudes of their advisers, on tyranny and its consequences, on

human cruelty, human frailty and human potential. All this he

did in a style apparently straightforward, easily assimilable;

the uncluttered affection that informs his writings has made

them for seven centuries a source from which ordinary

people have drawn advice, information and enjoyment. Yet

in his lifetime the Mongols came crashing out of Central

Asia, dismembering Persia and bringing to an end the great

centuries of Baghdad’s cultural supremacy. Seen against the

circumstances of history, Saadi’s urbanity, his humanity and,

not least, his lightness of touch, seem superhuman.

Yet Saadi, too, for all his ease of manner, saw the truth

as complex and many-layered. In him, this often expressed

itself through paradox and contradiction. There is no facile

consistency in the surface of his works; those wishing to refute

him can often find the arguments they need elsewhere in his

own writings. As a result of this, and of his word-play and

wit, those who read or hear his works are constantly forced

to become aware of the very act of understanding, and thus

both of the works themselves and of their own responses.

One cannot surrender to passive delight for long before some

change of direction, some unexpected profundity, joke or

reversal jolts one into intellectual activity. What this suggests

is that the consistency in what Saadi wrote lies at another

level and perhaps in another place, not in the works but in

those who receive them. In their complexity they are, it seems,

primers for self-development, instruments for the dynamic

alteration of consciousness. He was a Sufi in his sense of the

universality of religion, in his humanity, in his understanding

of the links between flesh and spirit, but above all perhaps in

this, that he knew that the value of what is taught lies in the

minds of those whom it reaches.

The work of Hafiz, too, has its unsuspected levels, its

complexities. Born some hundred years after Rumi, in Shiraz,

he was during his early manhood installed in a school of his

own, where he taught theology and expounded his theories of

religion. He lost his father when a young child, and later both

his wife and son. His poetry appears in the main a celebration

of romantic love, modified by his awareness of himself as

too old for such emotion. From this it has been inferred that

the bulk of it was written when he was aged. Whether that

is so or not, he was so acutely aware of the value of love

that he detested those who, as it were, clouded its brightness:

the censorious, the hypocritical, the sanctimonious, the

pedantically orthodox. He believed in the liberty of the

intellect and of the senses; no wonder that there were those

who thought him both profligate and heretic.

He, too, in his works ran the gamut of modes and feelings,

for his poems were licentious, mystical, humorous, satirical or

epigrammatic by turns. At the centre of his writings, however,

lie his cool, affectionate humanity marked by a dislike for

fanaticism, for the trappings of power and wealth – and his

mystical certainties. Addressing a man of property who had

attempted to add to his secular riches the acclaim proper to

one returning from pilgrimage to Mecca, Hafiz wrote, ‘Boast

not rashly of thy fortune. Thou hast visited the Temple – and

I have seen the Lord of the Temple.’ This is the nub of the

matter, and the certainty which that conviction gave to Hafiz

sustained him in a world where, in the wake of the Mongol

assault, social and political structures were collapsing, religion

had been coarsened and civilisation weakened, apparently

forever. It is the certainty of the mystic, and Hafiz shared it

with all the great names of Sufism.

In that list there are many more, stretching from the

10th century ecstatic Hallaj, crucified by the orthodox,

and the founders of Sufism in the centuries before, by way

of philosophers and poets – the chemist Fariduddin Attar,

the polymath Omar Khayyam and many others – solitary

saints, men in humble occupations hiding the secrets of

their serenity, great leaders, heads of dervish orders, to the

adepts of today. Yet for each neophyte setting forth on this

difficult path, the only important person, eclipsing all the

great, will be his chosen Teacher. It is the Teacher he must

trust, the Teacher who must know the right sequence of his

development, through the Teacher that he will discover the

intellectual and emotional adjustments necessary to prepare

him for the knowledge to come.

At first the knowledge will be short-lived, entering the

student at will, and leaving even if bidden to stay. ‘I staggered

to my feet and looked about me and tried to remember what

had until that instant been crowded in my brain and it was

all gone, all the details, covered over by the present and my

humanity as a flash-flood will cover the pebbles lying in the

dry bottom of an ancient creek. It was all there, or at least

some of it was there, for I could sense it lying there beneath

the flash-flood of my humanity. And I wondered, vaguely, as

I stood there, if this burial of the matters transmitted by my

friend might not be for my own protection, if my mind, in a

protective reflex action, had covered it and blanked it out in

a fight for sanity.’ But in the end, the altered self emerges into

the sought-for state of readiness, and the ultimate certainty

responds: ‘It was all there again – all that I had known and

felt, all that I had tried to recapture since and could not find

again. All the glory and the wonder and some terror too,

for in understanding there must be a certain terror... There

were many universes and many sentient levels and at certain

time–space intervals they became apparent and each of them

was real, as real as the many geologic levels that a geologist

could count. Except that this was not a matter of counting;

it was seeing and sensing and knowing they were there. Not

knowing how, but filled with mystic faith, we... took the step

out into the infinite knowing and were there.’

The quotations come from no mystic’s reminiscences, but

from a science-fiction novel, Destiny Doll, by Clifford Simak.

Those who think this inappropriate have understood very

little of what has gone before.

Sufi Studies and Middle Eastern Literature

Latest News, Blog and the ISF Podcast

Welcome to our latest news, blog and podcasts

![]()

Warning from The Subtleties of the Inimitable Mulla Nasrudin

Warning from The Subtleties of the Inimitable Mulla Nasrudin

From Idries Shah's The Mulla Nasrudin Corpus

The appeal of Nasrudin is as universal and timeless as the truths he illustrates. His stories are read, enjoyed and shared by children, scientists, scholars and followers of philosophy the world over. Idries Shah assembled perhaps the largest collection of Nasrudin’s trials and tribulations from sources across North Africa, Turkey, the Middle East and Central Asia. Gradually, these are being absorbed into Western culture. Some are no longer identified as Nasrudin stories at all!

Today’s story is taken from one of Shah’s four collections of infectious Nasrudin stories. ‘The Sufis, who believe that deep intuition is the only real guide to knowledge, use these stories almost like exercises,’ wrote Shah. ‘But [they] concur… that everyone can do with the Nasrudin tales what people have done through the centuries – enjoy them.’

Our Impact

Books for Afghanistan

In March 2020, 3,000 copies of the Dari Persian translation of Speak First and Lose by Idries Shah were distributed to schools and libraries across Afghanistan through our partner Hoopoe Books. Another 5,000 copies are being printed.

UNESCO Collaboration

Around 5,000 children between the ages of 12 and 18 participated in ISF-UNESCO’s first short story competition. The theme ‘Once Upon a Time In My Future…’ drew entries from as far afield as Chile, Iran and Mongolia.

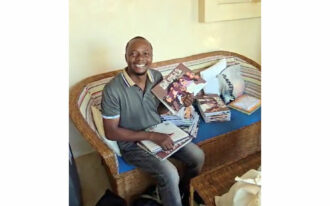

Taking Sufi Literature ‘Home’

ISF is making Idries Shah’s books available to readers in Asia and the Middle East, thereby ‘returning’ them to the societies that birthed much of the material he drew from. They are reaching refugees from Afghanistan and Iran – and now Turkish readers.